On October 26, 1963, a 12-kiloton nuclear bomb was detonated underground in Fallon’s backyard, 28 miles from City Hall, 20 miles from Stillwater, 12 miles from Salt Wells, 5 miles from Sand Mountain. Last week, I wrote about how and why that region had become a national atomic test site. This column touches on how the community reacted to its new and unusual role.

To understand the local response, we need to revisit the cultural context of the time.

The nation was in the middle of the Cold War, and almost everyone living in America feared the Soviet Union’s nuclear capability. The Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of August 1963 had just been signed, banning atmospheric testing and moving nuclear testing underground. Some of the visceral panic of the “duck and cover” days receded. We no longer regularly viewed ominous images of mushroom clouds as they rose from the dusty earth of the Nevada Test Site. Yet, the fear of a nuclear war remained deep in the recesses of a national consciousness, and everyone in America was urged—by the government, by the military, by the press—to do everything they could to keep our nation at the forefront of nuclear development and testing. Just months before the “Project Shoal” event, many Fallonites would have read an article in “Reader's Digest” by James A. Farly stating, “Communists are moving war toward us. Today, they are on our doorstep” (July 1963).

The Soviet atomic program was (understandably) demonized. At the same time, the American atomic program was (understandably) cast in a positive light, not just as a means to maintain an edge in case of warfare, but as a means to solve hunger and poverty and bring peace to the world. President Eisenhower, in his famous “Atoms for Peace” speech of December 1953, proposed that a pool of atomic materials be established to make the “deserts flourish” and help “to warm the cold, to feed the hungry, to alleviate the misery of the world.”

In light of these sentiments, “Project Shoal” was promoted to Fallon citizens as their national duty and their gift to humanity. Yet, even more persuasively and noticeably, the event was cast as a boon to the local economy. Local newspaper headlines avoided words like “bomb,” “radiation,” “blast,” and “nuclear,” instead proclaiming, “AEC [Atomic Energy Commission] to ask for Bids”; “Forty Miners will be Employed”; “Contractors Advised AEC to Issue Plans for Drilling Program.”

The Atomic Energy Commission launched an all-out public relations campaign on the streets of Fallon. They opened an office at 335 East Stillwater and invited the public to drop by. A diorama of “Project Shoal” was constructed and loaned to schools, the First National Bank, and the library. A public meeting was announced in the “Eagle Standard” on October 1, 1963, to “explain that a recent detonation which caused tremors in Las Vegas was many times as powerful as ‘Shoal.’” In other words, there was no need to worry about a triggered earthquake. The Public Health Service provided lectures and demonstrations explaining their extensive air and water sampling plans to, among others, the Lions Club, the Rotary Club, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, American Legion groups, and the public schools.

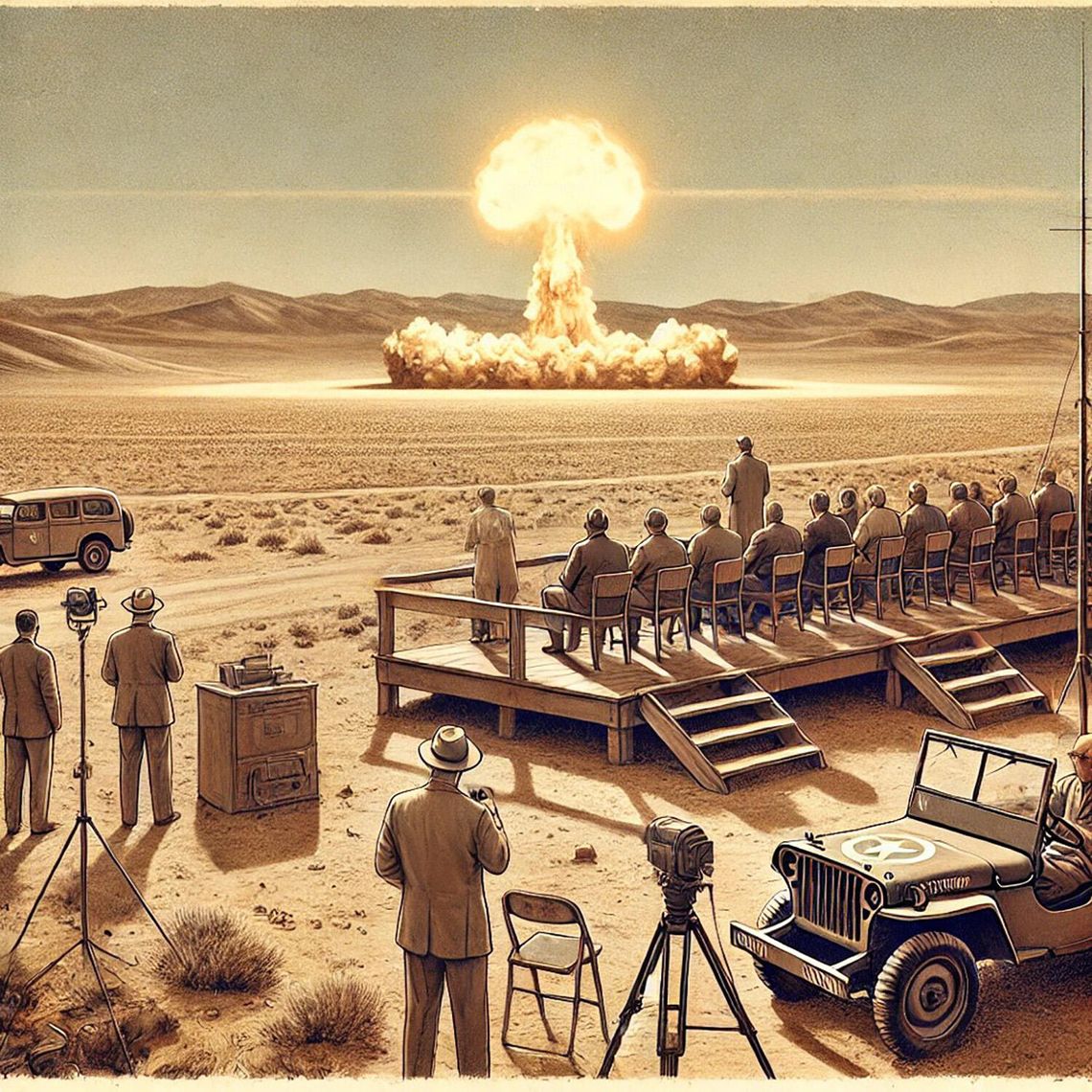

In retrospect, the most astounding feature of the public relations campaign was the erection of grandstands close to ground zero so that national, state, and local officials could view the moment of detonation.

Interestingly, there were no angry letters to the editor, no demonstrations, no protest groups. Mr. John Tudor of Reynolds Electric Company, an AEC subcontractor operating an office in Fallon during the planning and execution of “Project Shoal,” reported to the Fallon Chamber of Commerce about three months following the event that his company “had been very happy in their dealings with the community…. The cooperation had been excellent.”

Please send your stories and ideas for stories to [email protected]

Comment

Comments