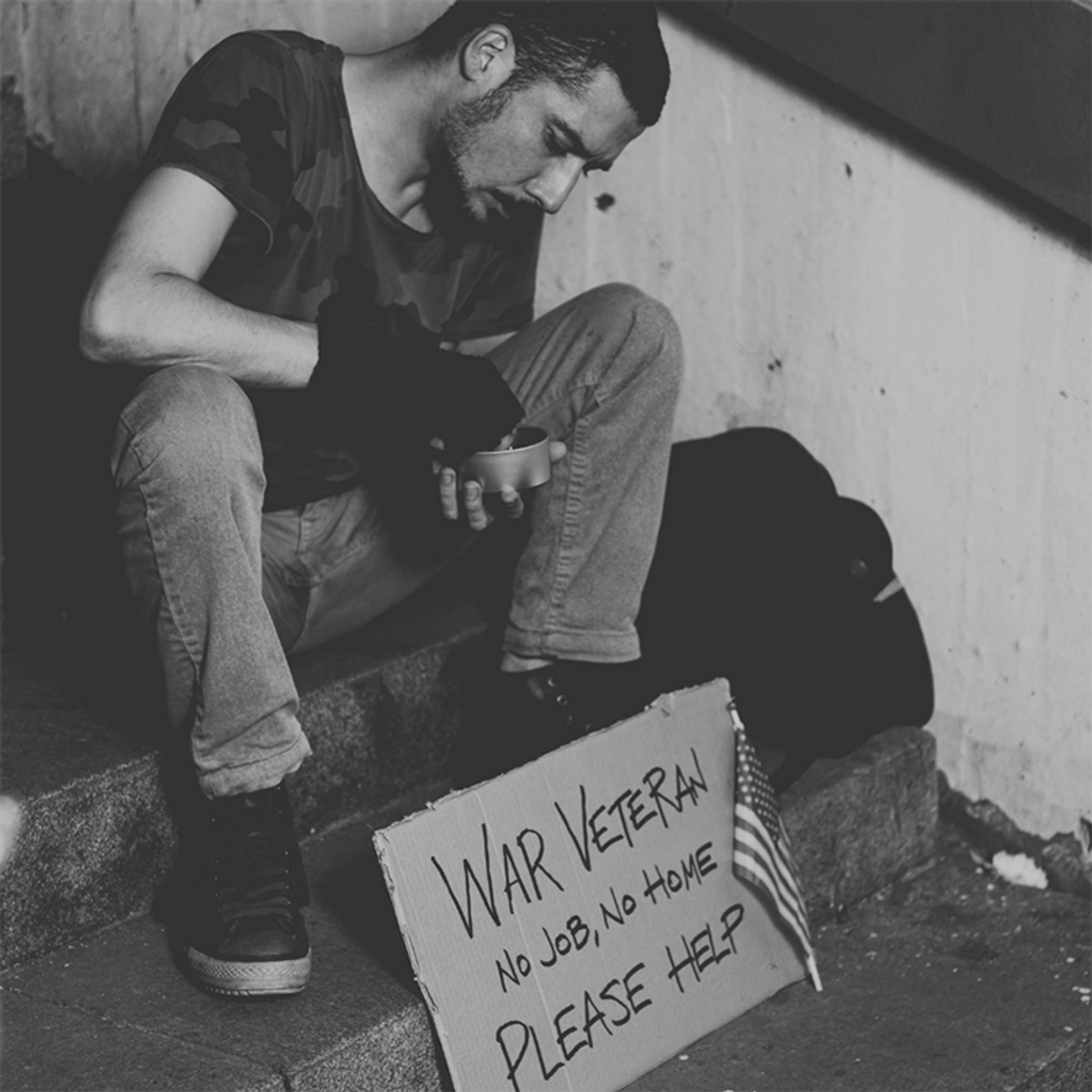

What is being done about the homeless? You have probably either heard this question before, or possibly even posed it yourself as Nevada's homeless population continues to explode. And it is not just the Silver State that is experiencing this phenomenon. Several other states, including those most Western, are also looking for solutions to a growing homeless population.

However, homelessness needs to be more fully understood before tackling the daunting problem of what to do about it. The most common perception of a homeless person is generally a dirty individual, alone and potentially mentally ill, wrought with mental addiction issues, and refuses to comply with societal norms. Yet most populations include a very diverse group of individuals making up the larger whole. Many homeless individuals may look as described, but are as individually unique as any other population.

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines homelessness in multiple ways and includes all ages of both sheltered and unsheltered individuals. Sheltered homeless include those in shelters, including domestic violence shelters, emergency and transitional housing, a hotel or motel lodging paid for by public agency or through private assistance, those doubled up in conventional housing with family or friends, and individuals in mental health facilities, chemical dependency facilities, or criminal justice facilities.

Unsheltered individuals, however, generally cause the majority of community concern. HUD considers unsheltered as those living in places "not meant for human habitation," such as cars, parks, sidewalks, abandoned buildings, and on the street. Nevada also sees homeless individuals living in rural locales on publicly owned land in tents, cars, and derelict structures, with its unique topography and comparably low population. Often, with no stable home, year after year, many of the unsheltered eventually become "chronically" or street homeless. Even individuals on public assistance that live in motels until they run out of money and return to the streets until their next check arrives are among those considered chronically homeless, according to HUD.

Unfortunately, chronic homelessness is on the rise. Unlike the sheltered homeless, where some may live in the shelter system for years, many chronically homeless persons often avoid shelters. HUD reports that these non-shelter users regularly sleep outdoors and in abandoned buildings, shanty-type structures, or tent cities and encampments. Some manage to live in RV parks and cars, if they can find areas where they are less likely to be noticed.

What is not widely known is that HUD defines chronic homelessness as something experienced by an unaccompanied homeless individual who is generally living on the streets or anywhere not meant for human habitation and has been continuously homeless for years. Or, they have had at least four episodes of homelessness in the last three years. Further, they have a disabling condition that may include substance abuse disorders, severe mental illness, developmental disabilities, or a chronic physical disability or illness.

Sadly, many chronically homeless with these conditions are afraid of shelters and largely congregated homeless areas. Instead, they can be frequently found at the fringes – along roadways and underpasses, in transportation corridors, and locations where they are unseen. This fact provides many challenges. The chronically homeless are also more reluctant to participate in data collection efforts than their sheltered counterparts. This is especially true in communities with a policy of providing homeless people with a bus ticket to the nearest city.

HUD states that they recognize the difficulty of collecting information on unsheltered homeless people in rural areas, places with few homeless resources, and across large geographic areas. Consequently, data collection in rural Nevada is uniquely challenging. The result is a lack of statistical accuracy when determining how many people live on the streets or are chronically homeless. The COVID-19 pandemic only aggravated the problem—recent attempts at gathering information yielded scarce results.

According to Shannon Ernst, Churchill County Social Services director, Social Services, in partnership with HUD, organizes an annual one-day homeless count in January. The Point in Time Count (PIT) is a physical count conducted in a single 24-hour period. Local law enforcement assists Social Services in observing homeless individuals, which provides a snapshot of the area's homeless situation at that point in time. The most recent Churchill County PIT count in January reported that there were only four unsheltered homeless and five sheltered homeless in the area. The school count indicated that 113 children were experiencing housing instability, and 28 individuals lived in motels or hotels.

According to Ernst, Fallon PD and FPST Tribal Police assisted with the January count. However, neither could locate individuals experiencing homelessness this year within their service areas during their shifts. Three motels participated in the motel count, reporting four households without children and one household with children were residing on a long-term basis, which is at risk of homelessness, per HUD. Those placed in Social Services housing programs on the night of the count consisted of one adult. Per HUD, these are considered homeless due to living in transitional housing.

Churchill was not alone when experiencing difficulties in conducting the PIT Count. In February, the Department of Housing and Urban Development published its most recent homeless report. However, because of what they called "pandemic-related disruptions to counts of unsheltered homeless people in January 2021," the report focused on only people experiencing sheltered homelessness. Even without complete data, HUD reported that Nevada has experienced a 260.7% increase in homelessness over the last 14 years. Nevada ranked only slightly lower than Colorado.

Adding to the cauldron of difficulty for the homeless and their communities, military veterans are experiencing more sheltered homelessness, despite a nationwide decline of about 54% since 2009. According to HUD, the January Point-In-Time (PIT) report found that 19,750 veterans were technically homeless in America, comprising approximately 8% of the nation's sheltered homeless population. About 15% of homeless veterans had experienced chronic patterns of homelessness. Nevada tied with California as having the third-highest rate of veteran homelessness, with approximately 22 out of every 10,000 people in Nevada a sheltered homeless veteran.

More men are reported homeless than women, although the number of homeless females is increasing. Nevada reported no change in sheltered youth between 2020-2021; however, a significant portion of the State's homeless youth are unsheltered.

While data is critical to understanding homelessness's many variables, it does not provide a solution. With homeless exacerbated by soaring rents, a lack of affordable housing, and skyrocketing inflation, it is not unreasonable to anticipate more homelessness in Fallon. Further, it is essential to remember homelessness is not a crime.

Churchill County Sheriff Richard Hickox stated last year that the homeless population has recently become more visible, increasing awareness. "Certain subsets of the community have prompted calls for us to check on the individuals (welfare checks), which we gladly do," said Hickox, "Other calls are for us to arrest or move them out of our county – which obviously we can't do."

Homelessness of any sort creates real problems. Often for the individual experiencing it and at times for the community where it exists. As the homeless population continues to increase, Fallon and many other states and towns will have to find ways to address these issues. But as for now, all we have is an extensive survey of the problem.

If you are experiencing homelessness or know others in need of resources, Churchill County has a host of resources available at http://falloncommunityresources.com.

Click here for details on the 2022 homeless HUD Report.

Comment

Comments