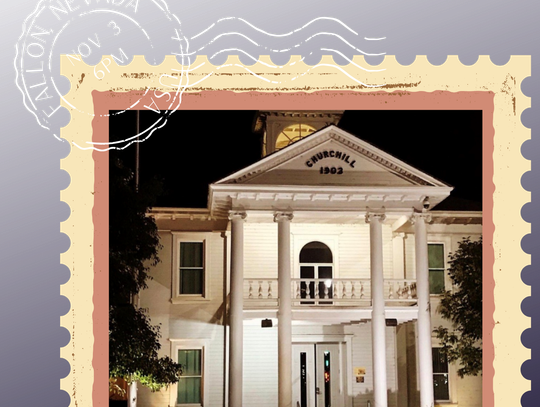

At midmorning on October 26, 1963 (sixty-two years ago), Fallon, Nevada, earned a permanent place in American nuclear history. At precisely 10 a.m., a 12-kiloton nuclear bomb was exploded 1200 feet beneath Sand Springs Range in a test named “Project Shoal.” Thus, official documents list “Fallon, Nevada” as the location one of only eight “off-site” atomic tests completed in the United States. “Off-site” implies an area not located on the former Nevada Test Site (NTS), 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas where a total of 928 nuclear tests took place, both in the atmosphere and underground.

Why was the Fallon region chosen as an atomic test site? The answer is complicated but derives, in part, from the fact that in 1954, an area close to the “Shoal” site had been the epicenter of a magnitude 7.0 earthquake. Underground atomic tests produce seismic signals, as do earthquakes. The Atomic Energy Commission planned to develop methods to distinguish a seismic signal created by an underground nuclear explosion from a seismic signal created by a naturally occurring earthquake. They hoped to be able to detect any secret illegal Soviet testing by examining the seismic signal. And, if Soviet Union officials claimed that the signals were from an earthquake, not a test, the AEC could effectively counter the claim. Conversely (I suspect), if the two signals proved impossible to distinguish, one from the other, the AEC might be able to claim that any signals produced by secret testing on their part were…from an earthquake.

Another factor in the choice of location for conducting “Project Shoal” was that the same region, earlier, in 1950, had been thoroughly examined by the military as a potential national atomic test site. In a study undertaken by the U.S. Army Special Weapons division called “Project Nutmeg,” an area in west-central Nevada, “about 50 miles wide and extending from Fallon to Eureka along Highway 50” was one of 5 sites nominated. As history shows, the Las Vegas-Tonopah Gunnery Range, to be renamed NTS, was eventually chosen.

A 12-kiloton bomb, like the one detonated near Fallon, is not a large nuclear bomb (a kiloton equals the explosive power of 1,000 tons of TNT). By comparison, the largest underground test undertaken by the United States was located at an “off-site” location in Amchitka, Alaska and yielded nearly 5 megatons (a megaton equals the explosive power of 1,000,000 tons of TNT). The radiation release from the “Shoal” explosion itself was minimal, but nevertheless some radiation was released in drilling performed later at the site in efforts to gather more data. The more pressing issue is that radioactive particles remain trapped beneath the surface, some of them very long-lived. Plutonium, for example, has a half-life of 25,000 years. Wells are constantly monitored and drilling near the site is forbidden, but we cannot accurately predict future water table levels and migration patterns of radioactive particles. Nor can we guarantee that future humans will not drill into the bomb cavity, releasing dangerous radiation. Yet, a visitor to the site today can find little evidence of its extraordinary role in atomic history.

Next week, I’ll tell the story of how the citizens of Churchill County reacted to “Project Shoal.” A spoiler alert: grandstands were erected at the site to provide firsthand viewing of the event by Atomic Energy Commission officials and our city and county officials.

Please send your stories and ideas for stories to [email protected]

Comment

Comments