Churchill County’s Sand Mountain, just to the north of Highway 50, some 25 miles east of Fallon, is often described as a “singing sand dune.” In the Middle East and North Africa, singing dunes are common, but Sand Mountain is reportedly one of only three in North America. A second North American singing dune, named the Crescent Dune, is located near Tonopah, Nevada, and a third, named Kelso Dune, rises from California’s Mojave Desert.

The songs they sing vary with the season, the humidity, the force and direction the wind, and any disturbance caused by man, beast, or Mother Nature. They range from sighs to vibrating moans to thunderous roars. Local resident, Margaret (Peggy) Wheat, now deceased, but known nationally for her pioneering work, The Survival Arts of the Primitive Paiutes, described the music of the mountain: “It sounds like rolling thunder. It’s absolutely quiet out there and then you can hear it clear down at the highway more than a mile away.”

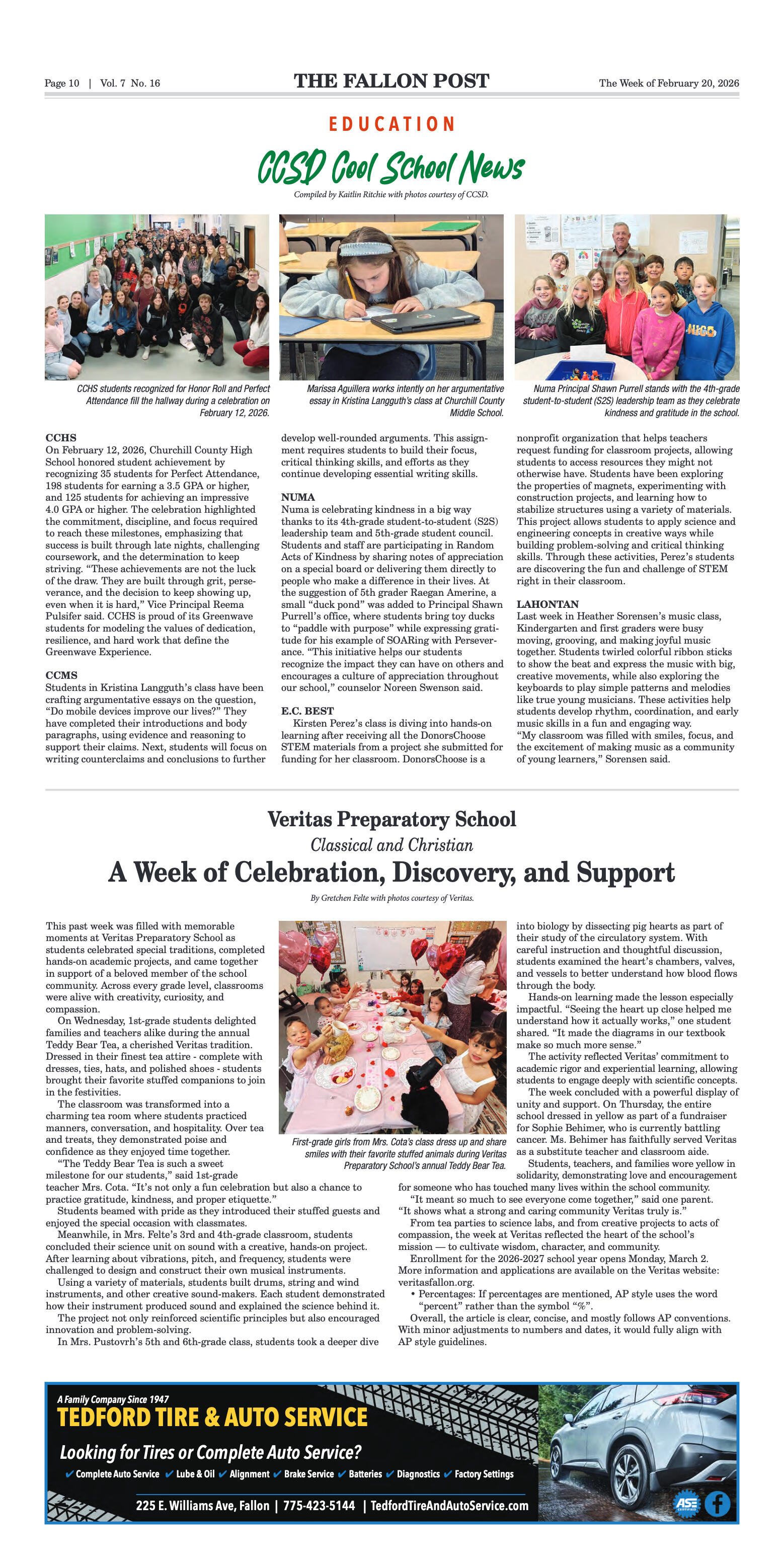

Helen Stone, a member of the local Paiute tribe, wrote that her people spent the summer in the hills east of here, then turned back in the fall to the Carson Sinks. They stopped at “the singing sand hill,” and “after the evening meal, they lay upon their beds; as it grew dark, the sand hill began to hum and hum so they listened…. Soon, they also fell asleep. They tell us the sand hill felt sad for the ones who were sick and tired, so he hummed them to sleep, to rest through the night.”

Writing in the July 1990 Lapidary Journal, Sharon Elaine Thompson reported that “according to an 1883 report on Sand Mountain… the sound was less like a lullaby and more like a Wagnerian opera belted out in an acoustically perfect hall.”

Theories abound to explain this unique and eerie phenomenon, including the Native American belief that the mountain was a living creature, who would roar angrily at times and murmur softly at others.

Scientists have differed in their explanations of the formation and characteristics of Sand Mountain, but they agree that the sands have blown to the site from the beaches of ancient Lake Lahontan, which dried up for the most part about 9000 years ago. Israel Cook Russell, a member of the United States Geological Survey Team in 1885 observed, “It is impossible to trace the sands….to their sources, but we may be sure that they have traveled far and were not derived from the waste of the rocks in their present neighborhood.” A prevailing theory is that southwest winds continue to deposit new sands blown from Weber Reservoir near Hawthorne through an opening in the Cocoon Mountains, through Simpson Pass, across the Four Mile Flat and, finally, against the rising Stillwater Mountains, where they pile up, shift, and add to the undulating wave of sand we call Sand Mountain.

The magic, the lore, and the desert songs of Sand Mountain now take second place to its fame as a recreation area. It is visited each year by at least 50,000 people who pay $40 per week to join in the fun of sand skiing, sandboarding, and riding all-terrain vehicles. The site is managed by the Bureau of Land Management and closely regulated. For example, 8 feet whip flags are required on all vehicles riding in the dunes; burning tires is prohibited; possession or use of any glass cup of bottle is not allowed; speed limit is 15 miles per hour in camping areas. What can’t be controlled is the plaintive song of the dune as it shifts, along with the times that have brought changes to it.

Thank you, Bunny Corkill, for writing a wonderful article on Sand Mountain, published in Volume 5, In Focus (1991-1992). You provided me with both facts and inspiration.

Please send your articles and ideas for articles to [email protected].

Comment

Comments